Below is a response by Tat-siong Benny Liew (College of the Holy Cross) to Amerasia Journal’s most recent issue “Asian American Religions in a Globalized World.” These thoughts were delivered at a roundtable about the issue at the recent 2014 Association for Asian American Studies annual conference in San Francisco, CA.

Let me congratulate Sylvia Chan-Malik and Khyati Joshi, first of all, for bringing us this long overdue sequel to 1996’s “Racial Spirits.” Elizabeth Cady Stanton was convinced back at the end of the nineteenth century, just when the U.S. was becoming a world power through its expansion into Asia and thus turned not only imperialistic but also xenophobic towards Asians, that the gender issue was more than a legal problem and could not be dealt with unless and until people were willing to tackle the question of religion as she worked tirelessly on her Woman’s Bible project. Despite, or perhaps because of Cady Stanton’s narrow understanding of religion as Christianity, this collection shows that we also need to talk about religion if we are to deal with the race question of this country adequately. For example, according to the 2012 Pew report, as an essay in this collection notes, up to 42% of Asian Americans surveyed are Christians, but the report of another national survey funded by the Lilly Endowment on the Bible and American Life that was just released last month does not even mention Asian Americans, though it does contain information on African Americans and Hispanics. Given this society’s “Christian normativity” and its tendency to “other” Asian Americans outside of Christianity, Chan-Malik and Joshi are on target to devote a major part of the issue to the theme and goal of “reorienting Christianity.”

Focusing on the intersection between Asian American racialization and religion, this special issue of Amerasia provides plenty of food for thought. For the sake of conversation, let me make three observations. While I appreciate the contribution on Hoodoo/Hindu conflation in the 1930s and 1940s to show that the global flow and transformation of bodies, goods, and religion for commercial profit have a much earlier history, as well as Chan-Malik and Joshi’s mapping of how the study of Asian American religions has developed in relation to Asian American Studies, I wonder if this sequel has done enough to address the current state of “a globalized world.” Many might debate if this globalized world is “postracial” and/or “postsecular,” but few if any would question if technology has been key to today’s global connections and operations. In this issue, Chan-Malik and Joshi mention “digital networks,” and Maryam Kashani, in a roundtable conversation that was conducted through Skype, mentions reading and writing about a Facebook debate on the terms “American Muslim” or “Muslim American,” but there is no exploration into what this globalized and digitalized—or digitally globalized—world might imply for the study of Asian American religions. Rachel Lee, Cynthia Sau-ling Wong, and Lisa Nakamura started talking about race in cyberspace over a decade ago, and scholars of religion have also raised questions about the impact of cyberspace on religion around the same time. In a chapter titled “Cyber-Spirits,” John Caputo claims in his 2001 book On Religion that religion is “flourishing in a new high-tech form, and. . .entering into an amazing symbiosis with the ‘virtual culture’.” Robert Geraci’s book Apocalyptic AI is not only subtitled “visions of heaven in robotics, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality,” but also argues that transhumanism—which has, by the way, come to a theater near you in the film, Transcendence—is “compet[ing] with religions. . .as a religion,” because while transhumanism “may deny the existence of one or more specific gods,” it does not “deny the existence of godhood, itself.” For Geraci, second life, with its “separation from profane existence and the existence of meaningful communities,” has become a “digital paradise” with a “sacred aura.” Just to give one more example, in 2004—yes, a decade ago—the Pew Internet and American Life Project reported that 64% of the 128 million adult Americans who went online had done so for religious or spiritual purposes.

We have learned from Iwamura, Joshi, Suh, and Wong in this collection that the Pew reports are far from innocent, and I am not invested in defending or siding with any particular reading of cyberspace or cyber-religion. Cyberspace has interested Asian Americanists and religion scholars separately since the beginning of the twenty-first century, so it should be a potentially productive place for the study of Asian American religions in the globalized world of this time. In this decade, we should be looking into cyberspace not only because it is not necessarily postracial and most likely postsecular, but also because it might be one place where we can learn something about the so-called religiously unaffiliated, especially when they, despite the biases of the 2012 Pew report, supposedly represent the second largest group of Asian Americans surveyed. In doing so, it might also help us break open and rethink our understanding and definition of religion.

This leads me to my second observation after reading this wonderful issue. While Iwamura, Joshi, Suh, and Wong repeatedly point to the 2012 Pew report as being limited by Western understandings of religion in general and Christian normativity in particular, the issue itself never moves beyond what has been recognized by the West as religions, so one finds after their entries on Islam and Hinduism a whole section that has to do with Christianity. In fact, even Iwamura, Joshi, Suh, and Wong’s critique of Western categorizations and understandings of religions seems to be limited to how Asian Americans practice these recognized religions differently, such as how Asian Americans might have a more communally oriented and less meditation-focused version of Buddhism, or how Asian Americans might challenge Arthur Darby Nock’s work in the 1930s by practicing what Nock calls religious conversion and religious adhesion at the same time, rather than seeing them as mutually exclusive; for instance, someone like Peter Phan would talk about being a Catholic with multiple religious belongings and reading the Christian Bible interreligiously, and got himself into a heap of trouble with the previous Pope. This limited critique may be seen also in their suggestion to Pew to group data on “ancestral spirits, spiritual energy, yoga, reincarnation, and astrology” under the heading of “Spiritual Matters”; their suggestion was rejected, though the Pew report does at times use the phrase “Other Spiritual Matters” to refer to this part of the report.

The othering dynamics here is not lost on our contributors, but their suggestion to call these data “spiritual matters” rather than something religious suggests that they might be repeating a very Western understanding of religion that is reflected in another popular phrase of white America: “spiritual but not religious.” I do not have time to unpack all the Western assumptions about religion behind this popular phrase, so let me go to another aspect of this, my second, observation. Given Iwamura, Joshi, Suh, and Wong’s point about Taoism and Confucianism not being included in the Pew survey because they don’t fit Western categorizations of religions, it would have been a nice, though admittedly not a very radical, move to have an entry on either of these religions in Asian America. (Editor’s note: The entries to the special edition reflected the subjects addressed by the submissions responding to the initial call for papers.) Just as we see race as a construction with changeable meanings, Asian American study of religion should not assume we know what religion is and what being religious means. Instead, it should use our study to keep interrogating the constructed meanings and definitions of religion.

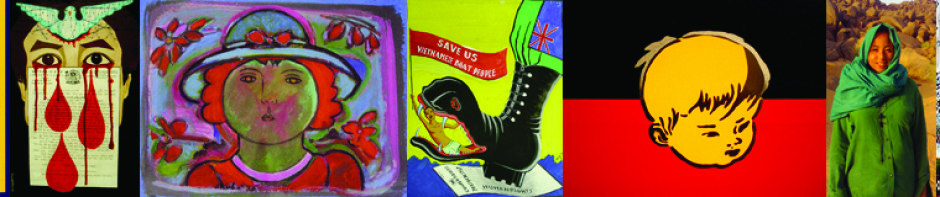

Third, I am impressed by, but do not really know what to do with, Busto’s attempt to reorient Christianity, and it has nothing to do with my disorientation caused by Busto’s surprising but superb engagement with Christian theology. I am impressed by his course, which looks absolutely amazing with its quote from Moffett as well as the slides of Polly Bemis and a Chinese-looking Madonna and the Child. I am also impressed by Busto’s comparison of inculturation, indigenization, and syncretism, as well as by his goal to move beyond the two-party Protestant paradigm of liberals and evangelicals, to unite Asian American Christians, and to present Asian American and Christian identity as mutually constitutive rather than inherently competitive. Despite Busto’s allowance for different thicknesses, various proportions, and the interchangeability of what is husk and what is kernel, though, I am not clear how his use of Harnack’s kernel and husk is free of the dialectic assumptions in the talk of inculturation, indigenization, and syncretism. After all, the reference to kernel and husk assumes two entities that are in the final analysis separable, and it gets worse as kernel is often read as the edible and nourishing content and husk as the disposable exterior or container. It remains stuck, in other words, in what Busto calls the two-party paradigm, even when the parties involved toward the end of his essay have become Christianity on the one hand and other religious traditions, especially Asian ones, on the other. To quote Busto quoting Swatos, this paradigm assumes or “believes that there are two parties and act on that basis.” Just as Busto wonders if the focus on the second generation actually reinforces the idea of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners, I wonder if his duplication of the two party-paradigm does not end up replicating Moffett’s move in giving Christianity an Asian origin only to, as Busto points out, detail its demise in the fifteenth century and then its dependence on Western Christianity since the sixteenth and thus normalize Christianity as Western.

What if Moffett’s point about Christianity’s origin in Asia is more than geographical? What if Asian religious traditions and Christianity were always already mixed at the beginning? What if Christianity was always already a syncretic movement with Asian religious traditions from the start? Unless you are a so-called Macionite, Christianity’s roots in Judaism should not be in dispute, and Judaism’s ideas about resurrection, heaven, and hell—topics which the Pew project, with its Christian assumptions, readily accepts—probably came from Persian Zoroastrianism because of Persia’s colonization of Israel from the sixth through the fourth century BCE. Let us not forget that Persia is, generally speaking, today’s Iran, so it is part of West Asia, even if the word “West”—unlike East, South, or Southeast—is rarely seen together with the word “Asia.” Similarly, virtually every introduction to the New Testament mentions Hellenization and the influence of the Greek empire. Let us not forget also that Alexander the Great’s empire reached as far as India and many scholars from India have argued that John’s Gospel contains many ideas that sound Buddhist. Asian religions have always already been inside Christianity from its beginnings. Quoting Fumitaka Matsuoka and describing hybrid, overlapping “amphibolous” practices of the Christian faith as “new,” Busto risks reducing the meaning of “reorienting Christianity” to something like a second-generation movement that we do now, rather than something that has always already been happening and that we must continue to do.

Amerasia on Facebook!

Amerasia on Facebook!